Posted by Karlyn Hixson on Apr 16, 2019

Q&A with Bruce Craven, author of Game of Thrones-inspired 'Win or Die'

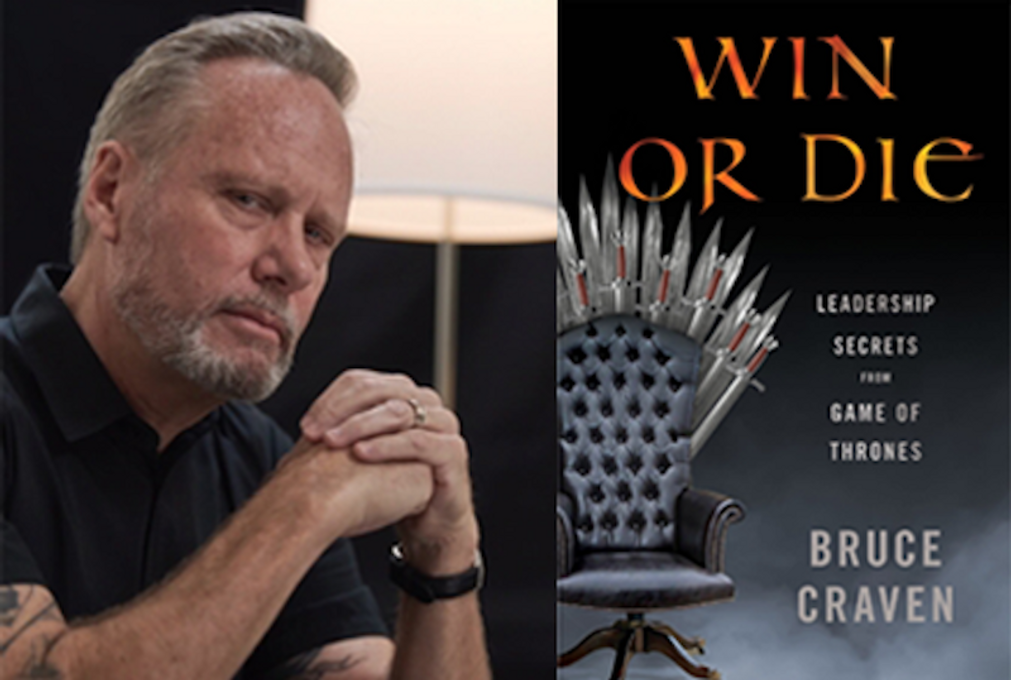

[caption id="attachment_30951" align="alignnone" width="800"] Photo by Mark Shaw[/caption]

Photo by Mark Shaw[/caption]

What Game of Thrones can teach us about leadership.

What better way to celebrate the return of the final season of Game of Thrones than with a Q&A with Bruce Craven, author of the recently published title, Win or Die: Leadership Secrets from Game of Thrones. Bruce teaches at Columbia University and in the summer of 2012, he launched a Columbia MBA elective course entitled Leadership through Fiction. The class uses novels, theater plays, and feature films as the source material to study issues of leadership. The popular course continues to run twice per year to MBA and Executive MBA students.

Without further delay, let's dive in to learn more about one of our favorite new titles!

You have some great insights about coaching and about steering clear of a coach that acts as a "vampire"—a coach who is more focused on the promotion of his or her own intelligence as opposed to the process of helping a coachee learn, grow, and make better decisions. What's your best advice to people seeking out a coach or a mentor? Are there particular characteristics they should look for in a coach, or be wary of?

I think it starts with someone that can be present and has the ability to step into the moment and listen, and not fall in the trap of being proscriptive. A short phone call with a potential coach should provide you with insights on how well they are listening. Are they repeating back what you're saying in order to acknowledge they hear you? Are they asking you questions that help you step down from the ladder of inference and challenge your negative thinking and subjective biases? I would look for that level of focus on you as the client, and look less for their promotion of their coaching capabilities. Basically, are they asking questions…and can they explain their process to you? And do they sound genuinely interested in starting a process that that is about your individual development? From an EQ perspective, I always connect better with someone that can be honest about their own strengths and areas for growth. I am more likely to trust someone that can provide perspective on themselves, as opposed to acting perfect.

My experience of being coached at different times, both formally and informally, is that the more the person was genuinely empathetic and challenging, but not trying to “fix me” from a perspective of knowing what was good for me, the more likely they were to help an idea land with me, whether that idea generated with me, or was searched out with their support.

When I coach, I always repeat to myself the Miyamoto Musashi line I reference in the book: “Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.” As a coach, I want to be as focused as I can be on being present, not caught up in myself. I want to be open to what unfolds in the conversation. I see the coachee as the expert and myself as a facilitator who can bring a bit of an edge, and rigor but also empathy… and some humor.

How does one best assess what is important to others in his or her immediate professional environment? In Win or Die, you write about how Ned Stark didn't fully understand the "reality of the relative importance of multiple values, of value hierarchies, and how these differently ordered systems guide the action of various people vying for influence in the Seven Kingdoms." Had he understood this better, do you think he would have made better decisions and ultimately lived?

I don’t think there was much values coaching going on in the Seven Kingdoms, so it’s not entirely fair to judge Ned on his lack of clarity around his values hierarchy, but it is fair to judge Ned on how transparent he was in his judgments of his colleagues. He strides into the Small Council and hugs the people he likes and is disdainful to the people he doesn’t trust. This makes it difficult for Lord Varys to build a bond with Ned. The Spider doesn’t want to extend too much information to a new leader that has already appeared to judge him negatively. Ned’s transparency isn’t strategic; worse, it’s not effective! Petyr Baelish isn’t troubled by Ned’s judgment. He is confident he can turn Ned’s distrust of Varys and others to his own advantage. When we enter new environments, snap judgments might feel comforting, but they don’t help us build our network.

In terms of values hierarchies, Ned saw that King Robert had embraced his role as monarch by pursuing his personal pleasures. Ned’s wife, Catelyn, pointed out to Ned that King Robert only stopped eating when he started to drink. This behavior doesn’t mean King Robert would be a bad leader, but when King Robert says to Ned that he wants Ned in King’s Landing to take care of all the boring leadership responsibilities the King wants to ignore, Ned could have pushed for clear guidelines on what Ned should consider his own responsibilities versus King Robert’s. The two men shared extended good-will towards each other, but they didn’t communicate effectively, either one-on-one or in team meetings. We can’t assume our good-will for people is the same thing as effective communication. Good-will can evaporate quickly if people don’t work to nurture mutual understanding.

You discuss the Finnish concept of "sisu" in Win or Die. Can you elaborate more about what that is and how an understanding of this can help people achieve greater successes?

Sisu, like grit, is a social construct, an idea created by people in a society. The surviving characters in Game of Thrones have survived for a variety of reasons, but all of them have had some ability to operate with resilience. Arya develops incredible skill at fighting with weapons. She learns from a variety of coaches. She operates with what Angela Duckworth calls grit. In her book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, Duckworth has a line that I don’t believe I used in Win or Die, but that I like very much: “If we stay down, grit loses. If we get up, grit prevails.” She defines grit as a tenacity we can access when we merge our passion for something (in Arya’s case, warrior skills with weapons) with perseverance (in Arya’s case, her perseverance is a constant, but one example of her perseverance is when she attempts to become a trainee for Jaqen H’ghar at The House of Black and White). She won’t take no for an answer. Grit relies on bringing the two together. According to Duckworth, sisu “is really just about perseverance” (pg 250)… but it’s an intense burst of perseverance.

In my teaching to senior executives and graduate students, it’s become clear to me that people need ideas they can put in practice when they are under pressure. Arya’s passion for fighting is not what’s driving her when she’s been chased through the streets of Braavos by The Waif. Arya wants to survive. Arya wants to win and not die. The social construct of sisu can be the idea we pull out to guide us when our backs are against the wall and we want to make it through… and our sheer passion is tapped out. When I was in the final stages of writing Win or Die, I continually reminded myself: “This is the time for sisu. This is a time to bring together a bravado that you will finish… with a ferocity to win.” We often have to lead ourselves and sisu and grit are concepts to help us bring out our most sustainable level of commitment.

Can you discuss some of the key differences of a truth v. judgment decision, and provide us more insights on this with Game of Thrones references?

If a person faces a decision and is confronted with an undeniable truth, there is a moment of epiphany. The truth has been identified, the answer is clear, and the decision is usually obvious. However, most often in business and leadership, we are confronted by the challenge to encourage people to understand the judgment we have arrived at on a subject. We are not presenting an absolute truth. We can easily fall into the trap of arguing as if we are presenting the “truth”—when we are really presenting a “judgment” of the best decision to make. It is better if we realize we are operating in a judgment area. We need to persuade people. We will fail if we continue to present our judgments to people forcefully as if we are sharing an undeniable truth. Recognize you are attempting to persuade people of your belief.

When Daenerys steps out of the Dothraki funeral pyre, her dragon eggs have hatched. She has dragons. Her dragons are a truth. When she discusses with her team on Dragonstone in the Chamber of the Painted Table the right military approach for Westeros, she and her team are involved in a judgment decision. It is a truth that she has dragons, but it is a judgment decision on how she and her team should use the dragons in battle.

What are you most hoping Game of Thrones fans and business professionals alike will gain from reading Win or Die?

The book offers specific techniques to help leaders guide themselves and their colleagues to confront adversity and achieve their goals. The book will work to guide a CEO at the top of a global organization, and the book will also work for a high school student who faces his or her whole professional future. I expect to see the book in boardrooms, on subways, and on the grass next to college students.

The exercise at the beginning of Win or Die about determining and ranking your value set is particularly useful (both personally and professionally). What would you say are the most important things for leaders to do and/or know in order to be most effective for their organizations and for ensuring future successes?

We will act to fulfill our values. It is important to understand them, in order to recognize if leadership opportunities are aligned with our values. If you take a certain role, is there a significant chance it will satisfy your values? If so, that is a job or role you should consider. If it won’t, you should realize it might still be worth doing, yet it will require leading yourself consciously through the process and you might find the work and the result unfulfilling.

Also, if you know your values, you can choose to reflect on them at times of pressure to be clear on what decisions will motivate you. You can guide yourself to act with authenticity by reminding yourself of your values when you are under pressure.

Win or Die is a definitive resource for not only Game of Thrones fans, but for business professionals looking for additional examples of what can happen when things go wrong (both fictionally and in real life). If you'd like to leave us with any additional thoughts about writing this book and/or what people will be able to gain from purchasing and reading it, we're all ears. Thanks for this and for your time!

I had two goals when I wrote the book: first, I wanted the book to energize the reader through connecting learning opportunities with the intensity and entertaining world of Game of Thrones; second, I wanted to share ideas from different professors that have helped me—and continue to help me—in my personal and professional life. I have seen the ideas I share in this book work! These professors helped me find my path forward against adversity: both internal doubt and external competition. We can all choose to be leaders for ourselves and for our teams. Win or Die is meant to a guide-book to help people achieve their aspirations. Valar Dohaeris!

Thank you, Bruce, for giving us a peek into your writing process and lessons to be learned from Win or Die. Whether you are a die-hard Game of Thrones fan or just in need of a new business book, this one is for you. If you'd like to purchase 25+ copies for your team or organization, please visit Win or Die on our website or feel free to contact us for a quote at support@book-pal.com.

This post was written by Karlyn Hixson, Marketing Director at BookPal. She is currently reading The Snowball System by Mo Bunnell.